Climate change and the pharmaceutical industry: too little, too late?

15 November 2022

Governments and companies across the world have made ambitious commitments to reducing their environmental impact. For example, 55 countries at the COP26 climate change conference in November 2021 committed to developing low carbon health care systems; and 20 have committed to developing net zero healthcare systems, with deadlines ranging from 2030 to 2050[1]. What is the pharmaceutical industry doing to help meet these targets, and is it enough?

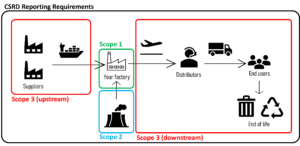

Government pressure on companies to improve their sustainability is rising; for example, in the EU, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive begins to take effect from January 2023[2], expanding the number of companies required to report their emissions and the scope of that reporting. Mandated reporting will now include Scope 3 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, as well as requiring third party assured reports, which must also be computer-readable. These laws will apply to large or listed companies within the EU, including non-EU companies with significant activity inside the bloc.

Figure 1: An illustration of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions in a value chain, with definitions of the different scopes3.

Altogether, these new requirements will significantly alter the landscape of climate-related reporting. It will be significantly easier to investigate the environmental impact of a company, and to hold them to account.

Globally, the healthcare industry accounts for approximately 5% of emissions[3], but unlike other, less necessary, sources of emissions, such as air travel for leisure, we cannot reduce emissions from the healthcare industry by simply reducing the amount of activity. At Springboard, we have carried out investigative assessments of healthcare products’ environmental impact. Especially in patient-led

care, we found that despite apparently having large environmental impacts, good early interventions, such as pMDIs, in fact avoid more harm by preventing more serious interventions later on[4]. A more nuanced solution is required to reduce emissions in this industry.

Public commitments

Of the 10 largest pharmaceutical companies by sales, all have committed to reducing their environmental impact. Some began reducing emissions as early as 2000, but some have only begun making serious, quantified commitments from 2019 onwards. Predominantly, these commitments focus on CO2 equivalent (CO2e) emissions, plastic waste or water use, within the operations of the company – that is, Scope 1 or 2 CO2e emissions, and plastic waste or water use within the direct control of the company.

Some of these targets are highly ambitious, such as Novartis’ target to be carbon neutral across their entire value chain by 2030[5], or AstraZeneca’s ‘Ambition Zero Carbon’ to be carbon negative across their entire value chain by 2030[6]. Some are less ambitious, with later deadlines and smaller reductions.

Only 7 of these emissions-based commitments were accredited by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi)[7]. The SBTi encourages companies to set net-zero science based targets and assesses whether targets are in line with a 1.5 °C future. Across the industry the general trend is to make large commitments on the easy wins, focusing on a company’s own operations, with more limited commitments in more difficult areas, such as Scope 3 emissions or water use.

Scope 3 emissions, however, made up approximately 80% of reported emissions from these companies. Figure 2 illustrates some typical proportions of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. Scope 3 emissions are still a consequence of the company’s actions, and to a great extent can be changed by decisions within the company. Given that Scope 3 emissions are the majority of the total emissions involved, meaningful targets must involve Scope 3. The largest quantified Scope 3 reduction target we found was 50%, and a typical target was 20%.

![An illustration of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions in a value chain, with definitions of the different scopes3.]](https://www.springboard.pro/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Figure-2-300x294.png)

Figure 2: An illustrative graphic of the typical proportions of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions among the top ten pharmaceutical companies.

Changes are being considered or implemented from the level of individual devices or manufacturing sites, all the way up to business-wide strategy. Several methods are being used to try and get emissions down – such as designing new products[8], improvements to the manufacturing process[9], or the Energize initiative[10] to enable suppliers to buy renewable energy collectively. Some companies have also installed renewable energy generation directly on their own sites.

GSK, for example, is altering some of its synthesis pathways to use enzymes, delivering massive efficiency savings. Johnson & Johnson has changed some of its packaging; the materials and methods were novel to the pharmaceutical industry and the change required serious investigative work to meet regulations. This is a good example of the scale of change required: on average, these 10 companies still need to reduce even their scope 1 and 2 emissions by half. In a highly regulated industry such as pharmaceuticals and healthcare, these changes take time, and must be started now.

Progress: too little, too late?

Are these efforts succeeding? Among corporations across other industries, the outlook is poor: large companies are failing to meet their emissions targets, by as much as 60%, and a report from the New Climate Institute found that none of 25 large companies they investigated in 2021 were achieving a high standard of improvement[9].

Among pharmaceutical companies specifically, progress so far has been mixed. A few companies have set climate related targets as early as 2010 or 2000. GSK for example, set a target of reducing water use by 20% between 2010 and 2020, and reported a successful 30% reduction in 2020[10]; Merck, similarly, aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 10% between 2010 and 2015, and

managed a 13% reduction[11]. However, other targets were not met: 7 out of the 10 largest pharmaceutical companies either failed to meet, or failed to report, the outcome of at least one of their targets. Some only fell a little short: for example, a target to reduce waste to landfill by 100% only reduced waste by 85%. Others failed badly, such as one company which published a target to reduce water discharge by 4% over 2 years, but actually increased water discharge by 15%[12].

Several companies have stated openly that they will use carbon offsetting or compensation, despite the well documented issues around these practices. Firstly that we already need to urgently decarbonize our economies and further reduce the amount of carbon dioxide already in the atmosphere by capturing carbon[3]. The second issue is that carbon offsetting methods are widely unaccountable, with flaws including:

- A lack of additionality, where credits are issued for carbon offsetting that would have occurred anyway, and

- Carbon “leakage”, where credits are issued for halting an activity which actually continues in a different location[13].

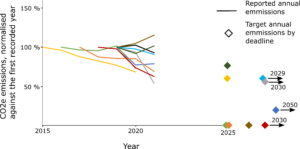

The work that remains is daunting but necessary. The typical reduction over the last two reported years was 7% for Scope 1 and 2 emissions, and only 6% for Scope 3 emissions. Five of the ten largest pharmaceutical companies increased emissions over the last two reported years. Figure 3 shows the reported Scope 1 and 2 emissions, where available, since 2015, normalized against the first reported year, and the targets that these companies are aiming for. Among the companies we investigated, the average reduction in Scope 1 and 2 emissions they needed to make, every year from now on, to reach their target, was 15%. Some must make reductions as large as 25%.

Figure 3: A graph showing the reported Scope 1 and 2 emissions from the top ten pharmaceutical companies, where available. The emissions are normalised against the first reported year’s emissions. The diamonds indicate the target annual emissions these companies have committed to reaching.

Some companies seem to be struggling with the sheer scale of this task; for some of the companies in our study, emissions increased from 2020 to 2021. One was able to report a 53% reduction in water usage at one manufacturing site, but this took over a decade. Another company was able to report a 3% reduction in energy consumption, but only because natural disasters had closed multiple production sites14. Many companies are still assessing the true size of their environmental footprint, carrying out internal investigations and beginning conversations with suppliers. This is only the first step in reducing emissions, and as self-imposed and external deadlines move ever closer, the time available to make these changes is slipping away.

Of all the pre-COP26 targets we were able to find for our top ten pharmaceutical companies, only half were achieved.

What to do next?

Some avenues companies could explore include life cycle assessments of existing business strategies and devices; root cause analyses of inefficiencies, pin-pointing the main problems with a device or logistical set up; moving on to concept generation and feasibility assessments (including sustainability) for the solution; and potentially the entire product development process from blue sky concept generation to manufacture, verification and validation, where the changes are significant. Given that climate change has been on the agenda for over a decade now, most of the low hanging fruit may be gone already.

From Springboard’s experience, we know how important it is to have both breadth and depth of skills to tackle such problems. We have found that engineering and scientific expertise, alongside a strong understanding of the business objectives, regulatory requirements, and vitally, industry experience have all been needed in order to assess such problems, find workable solutions and implement them successfully.

Companies will need to develop industry-specific strategies around supplier selection and management, and to design products with the logistical and manufacturing implications in mind. Cold chain transportation, for example, is energy intensive, but could be minimized with thoughtful drug formulation and good device design. Similar savings could be made in a variety of device types if world-class expertise and insight are applied to the project during the early design stages.

The targets set at and around COP26 were a good and necessary start. As we move further into the 2020s, it is clear that serious effort from all parts of the pharmaceutical industry is needed now to meet the goals and minimise further climate harm. Following the implementation of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, many companies will be forced to quantify and report their emissions to stakeholders such as their shareholders, governments, and of course themselves.

If you recognize any of these issues and would like to discuss how Springboard can assist your organization, please get in touch with Catriona Eldridge at contact@springboard.pro.

Written by Catriona Eldridge and Omar Shah and featured in OnDrugDelivery.

References:

- Web page, COP26 Health Programme (https://www.who.int/initiatives/cop26-health-programme/country-commitments, accessed September 05 2022)

- Web page, The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) (https://plana.earth/academy/csrd-corporate-sustainability-reporting-directive, accessed September 05 2022)

- Watts et al, “The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate”, Lancet, Vol. 394, Issue 10211, p1836-1878

- Article, “Are governments banning the most environmentally friendly inhaler?”, OnDrugDelivery, April 2022, Issue 132

- Webpage, Novartis ESG Targets (https://www.novartis.com/esg/reporting/targets, accessed September 10, 2022)

- Press release, “AstraZeneca’s ‘Ambition Zero Carbon’ strategy to eliminate emissions by 2025 and be carbon negative across the entire value chain by 2030”, 22 January 2022

- Web page, Companies Taking Action, (https://sciencebasedtargets.org/companies-taking-action#table, accessed September 08 2022)

- Press release, “AstraZeneca progresses Ambition Zero Carbon programme with Honeywell partnership to develop next-generation respiratory inhalers”, 22 February 2022

- Report, GSK Healthy Planet Healthy People, September 2022

- Web page, Energize (https://neonetworkexchange.com/energize, accessed September 10, 2022)

- Article, “World’s biggest firms failing over net-zero claims, research suggests”, Guardian, February 06 2022

- Report, GSK ESG Performance Summary 2020, published March 2021

- Report, Merck Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG) Progress Report 2020/2021

- References available on request.

- Hilaire et al, “Negative emissions and international climate goals—learning from and about mitigation scenarios”, Climatic Change 157, 189–219, Nov 2019

- Article, “What is carbon offsetting and how does it work?”, Guardian, May 4 2021